By August Benzow and Kenan Fikri

Over the past several decades, the United States has made little progress in helping families in the bottom half of the wealth distribution accumulate assets and save towards retirement, as can be seen in the latest data from the Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts, which merges data from the Survey of Consumer Finances and the Financial Accounts of the United States. The data also underscore the opportunity cost of limited asset ownership for most Americans: Large segments of the population have been unable to meaningfully participate in, and therefore benefit from, the boom in asset prices underway since 2000. The slow progress on this front is especially apparent with respect to retirement savings or pension entitlements, where the bottom 50 percent of the country’s wealth distribution has barely advanced in decades.

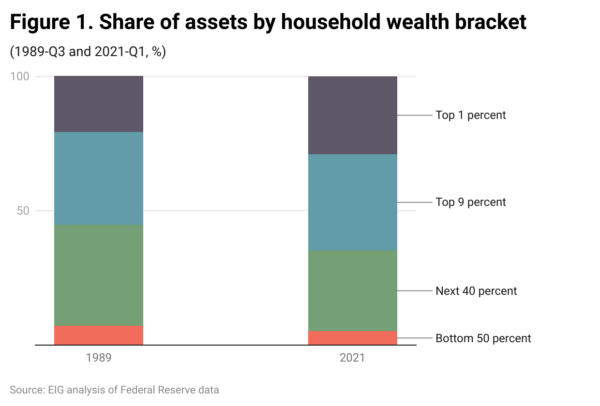

The bottom half’s share of national asset holdings is falling

In terms of total asset ownership, the bottom 50 percent of the country’s wealth distribution’s share of all household assets fell from 7.2 percent in 1989 to 5.3 percent in 2021. Meanwhile, the top 1 percent’s share of household wealth increased substantially, from 20.8 percent to 29 percent. The top 10 percent’s share of all household wealth in the United States is nearing two-thirds (64.8 percent).

Growth in retirement wealth for the bottom half has failed to keep up

Since 1989 (the first year in the data series), pensions entitlements have increased substantially for the top 50 percent of households and grown only modestly from a very small base for the bottom 50 percent. (Pension entitlements include assets in defined contribution retirement plans, the promises of defined benefit retirement plans, and annuities). Pension entitlements held by the top 1 percent have grown by 720 percent in nominal terms between 1989 and 2021, compared to 470 percent for the bottom 50 percent. However, these figures mask huge disparities in wealth accumulation. In dollar amounts, the top 10 percent added nearly $14 trillion to their total entitlements, while the bottom 50 percent added $716 billion ($11.4 trillion and $504 billion in real terms, respectively)一19.5 times as much. The bottom 50 percent’s share of total national pension entitlements actually fell over the time period, from 4.3 percent in 1989 to 3 percent in 2021. Put another way, of the $25 trillion in retirement assets accumulated over the period, only 3 percent belonged to households in the bottom half of the country’s wealth distribution. The top 10 percent of households, by contrast, claimed 54 percent of all new retirement wealth.

Older workers have seen much faster retirement savings growth than younger and middle-aged workers

In real terms, the prime age workforce has seen very little increase in pension entitlements since the late 1990s. That stands in stark contrast to older workers and retirees, who have seen their holdings grow smartly over time. As a result, younger households own a shrinking share of the nation’s pension entitlements. In 1989, total pension entitlements were split evenly between those with at least 10 more years before reaching retirement age (54 and younger) and those near or past retirement age (55 and older. Today, older households claim 63.5 percent of the nation’s retirement wealth. This cannot be explained entirely by the aging of the large Baby Boomer generation: using inflation-adjusted numbers, the per household gap between the younger and older cohort grew from $63,500 in 1989 to $160,700 in 2021 (Figure 3). The reasons for the prime age cohort’s slow progress are likely numerous but include the high costs of higher education (prompting households to service debt in early years or save for college instead of retirement in later ones) and less likelihood to have a defined benefit pension plan. Regardless of the explanation, however, the effect is clear: This delay in accumulating retirement assets represents a missed opportunity to enjoy compounding returns, which will compel younger cohorts to set even more aside in the years ahead or else see a reduced standard of living in retirement.

Convergence in pension assets across races and ethnicities is slow

In a sign of progress for groups typically left behind, real pension entitlements per household increased slightly faster for Black and Hispanic households over the period than for white ones. In 2021, both groups had 2.6 times the amount of pension entitlements compared to 1989, versus 2.4 times for white households. Despite this slightly higher growth rate, the average white household still had three times the pension entitlements of the average Hispanic household and two times that of the average Black household in 2021. White households claim 79 percent of all retirement assets, despite representing only 65 percent of all households. On current trajectories, the pension entitlements of Black and Hispanic households are not on course to catch up to white households for hundreds of years, if ever.